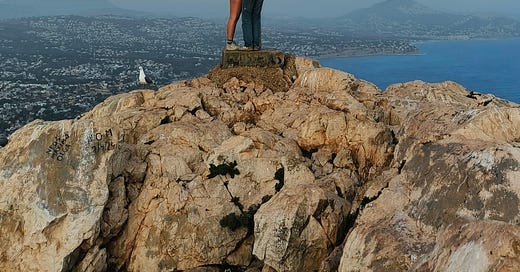

From our viewpoint, it looks as though the world is split in two. To my left, the North, and its undulating, patterned ocean crawling onto Calpe’s shore. On my right, from where the cardinal winds approach, the waves thrash wildly against the rocks below, and I feel those tugging impetuous gusts, telling me to move or get blown over. Even here there are small streaks of graffiti on the limestone, an inexorable Spanish trait. We distribute our sandwiches and rest, peeling clementines.

The Peñón de Ifach is a mountainous crag that runs a kilometer long, and a designated sanctuary for Costa Blanca’s rare, endemic, and threatened flora and fauna, its sprouting pink wildflowers and varying species of thyme, its swollen red buds on fragrant junipers. A sign tells us that shags will nest in the cliffside come spring and that the “seabeds are so extraordinarily well conserved that it is possible to discover invertebrates such as the cow snail”—I assume this is a big deal. With my plant identification app I begin to realize just how rare the plants around us are: as in, they only grow on this particular rock, the Ifach, and are identified by their indigenous Valencian names, such as the Canyeta D’or, a spiky orange herb.

A friend showed us edible white flowers that have traditionally proven essential in holistic medicines. To me, they taste like green onion, or maybe radish. She also brought us down into a reclusive cove through a series of old fishermen’s huts carved into the rock face, a path called Ruta de los acantilados, Ruta dels penya-segats (Valencian) or, Route of the Cliffs. Here there are sheds surrounded by the ashes of cooking fires, where locals traditionally gather and make paella against the water’s edge. She told me that much of the Valencian Community’s culture is hyper-commercialized in its biggest city, where I live. I’m just beginning to grasp the profound depth and soul of culture lurking beneath its oversaturated Spanish image. For example, its language: untouched by the vitriolic tourism of larger cities, many pueblos speak so much Valencian that students only begin learning Spanish in elementary school.

The reason for all of these threatened species is the rapid development of the land for sumptuous foreigner (or guiri) vacation homes. We took a wrong turn at one point and ended up in one of these desolate communities, it being winter and them all being summer houses for the English, Germans, and Belgians. As we walked the beach at sunset, our footprints were the first in the blank slate of sand. Spain is clinging to its ethnic autonomy in a moment of globalization so fierce it threatens to extinguish culture as old as the Ifach, whose name comes from the Arabic word “North” (Yfach) and the time when Islam controlled the Iberian Peninsula.

On Ifach, we are surrounded by gulls, who aren’t exactly calling but more meowing eerily. I trace my hands along the smooth, orange limestone that has been pulverized into shape by a millennium of rain. This geographic feature began developing 56 million years ago. Cast in the shadow of the peak above us, the path smells damp and earthy, a beaten morass amongst the wildlife and windswept pines.

The route turns precarious and slippery, with a chainlink handle for us to cling to. I feel a bit terrified, looking down at the sharp drop. When we reach the peak, we stare down at the city and its collection of cranes. From such a great height, I can’t help but feel as if I’m looking down upon a world that is completely foreign to me.

Thanks for your beautiful words

This is lovely, vivid, beautiful and sad. so glad you are writing and sharing it.